Much has been written about the ‘poetic vision’ of Les Murray (1938–2019), constituted as a mythical ‘Vernacular Republic’ version of Australia built from vignettes of social mores, milieux, anecdotes and quirks of character and speech, rooted in family and folk memories and celebrating nature and pastoral society (Gould; Headon; Leer ‘This Country’). The preoccupation with ‘vision’ rather obscures poems not concerned with the ‘Vernacular Republic’. Murray’s choice of subjects was eclectic – Ivor Indyk has aptly described Murray as an encyclopaedist – and if there is another touchstone of his ‘poetic vision’ it is his metaphysics of the miscellaneous: an idea of a divinely-inspired life-force manifested in the most unlikely experiences and situations. Recently, a persuasive argument has been made for the high significance of disability (specifically autism) among Murray’s concerns, not least a desire to redress the marginal status to which autistic people may be relegated by dominant social discourse. Autism was diagnosed in Murray’s son Alexander and Murray believed himself to be autistic (Alexander 25), but it has taken a new scholarly attentiveness to neurodivergence to perceive the condition’s full importance in his work (Tink). New insights such as these are likely to continue to arise as long as Murray’s work is read critically. Yet, if we consider Murray only thematically, we will reach a point beyond which the poetry fails to fit a unitary theory. There is one other major factor which has not yet – not quite – received the same attention, but which offers possibly the best prospect of understanding his work comprehensively. This is Murray’s idiosyncratic use of language in poetry, his style.

Murray’s career began with an expansive pastoralism that extolled rural life and the natural world as Australia’s nourishing and redeeming myths, but it ended with curt snapshots that barely held on to any myth at all. The poetry collections of his first and last decades might seem the work of different authors with different preoccupations, if their style had not kept their complexities, inventiveness and digressions familiar. Despite its consistency, Murray’s style is generally considered the adjunct or the consequence of his themes. The poems’ offhand manner, their apparent unpretentiousness, their often-comical formulations and their pithy colloquial idiom are treated as characteristic of the imagined ‘Vernacular Republic’. Likewise, Murray’s tendency to create metaphors and images by juxtaposing unrelated but strikingly apt details has come to be regarded as emulating autistic perception (Tink). These are sympathetic interpretations, but by the prevailing logic, to paraphrase Dylan Thomas, they construe Murray as having written towards that cast of language, not out of it (Collected Letters 147–48).1 That is, ‘vision’ is conceived as having preceded ‘voice.’

This discussion aims to begin reversing that tendency by asserting, again in Dylan Thomas’s words, Murray was ‘his medium first, express[ing] out of his medium what he sees, hears, thinks and imagines’ (Collected Letters 147–48).2 Themes and experience may be intrinsic but expressive material and its organisation are paramount. If we accept this premise as germane to Murray’s own approach to writing – and it is in tune with his eulogies of the poetic vocation, which present poetic language as a residue of synaesthetic trance (Murray qtd. in Mycak 22–23) – then we may focus several tendencies in Murray’s work which criticism has left under-investigated or unspoken. In presenting Murray’s style as the primary channel of his thought, I hope to provide some basis for practical inquiry into Murray’s development as an artist, as polarised views of the man himself recede into the past.

This kind of historical and aesthetic inquiry is aided by the collection of Murray’s papers in the National Library of Australia (NLA). The NLA’s holdings (MS 5332) include hundreds of draft poems and related documents dating from the period immediately after The Ilex Tree (1965) to work posthumously collected as Continuous Creation (2022). Via these drafts, it is possible to reconstruct Murray’s methods and techniques for rendering initial ideas into the language and forms of poems – turning thought into style. Equally important in the NLA’s collection are Murray’s scrapbooks (MS Acc 22.060). These are three immense leather-bound volumes in which, from the 1980s until his last years, he collected postcards, photographs, newspaper clippings and other printed matter that piqued his interest. Collectively known to Murray, his family and close friends as ‘The Great Book’ and deposited posthumously at the NLA in 2022, the scrapbooks were described in Peter Alexander’s biography of Murray as ‘a symbol of his vastly eclectic interests’ (255; see also Grant xi–xii).

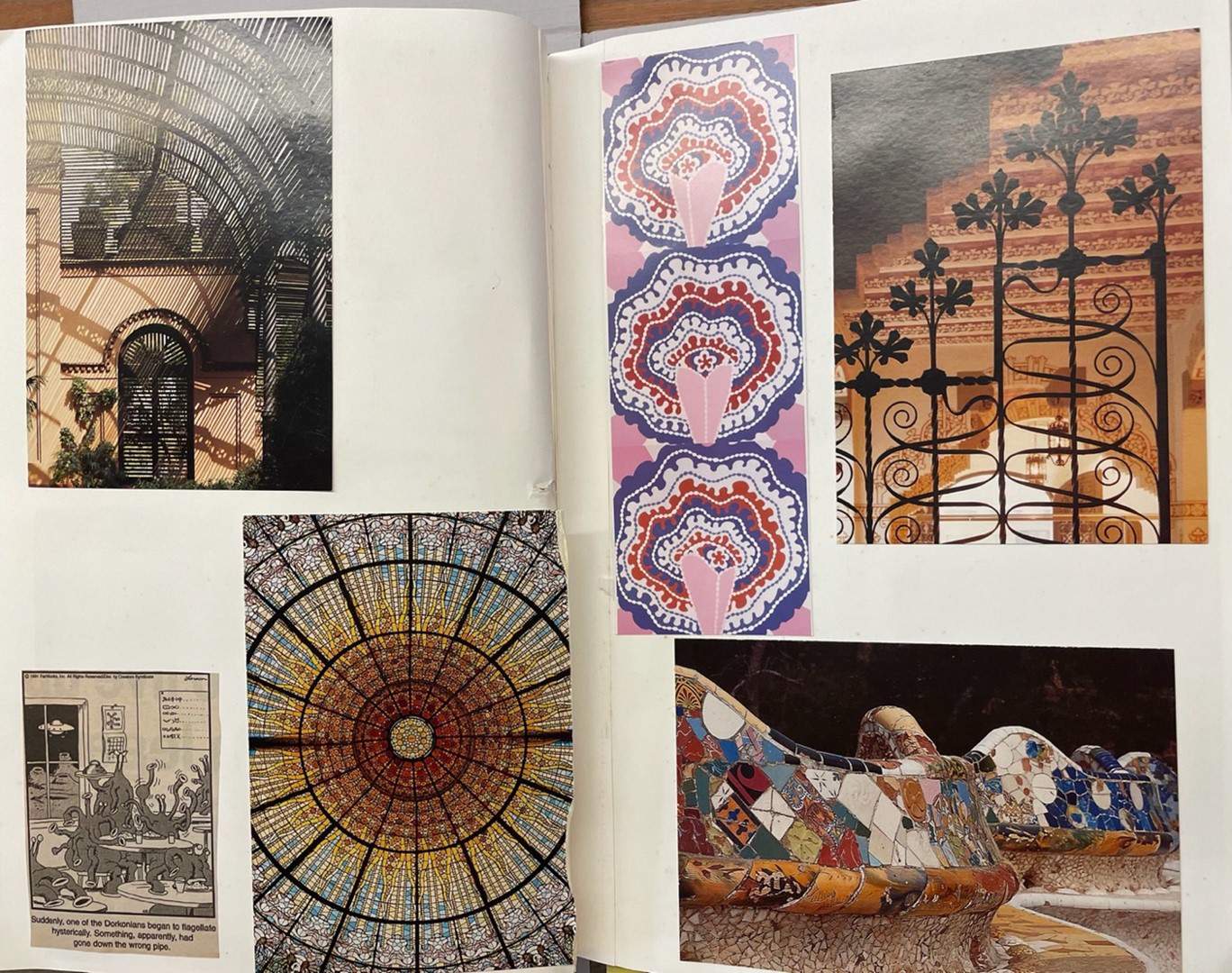

Symbolic the scrapbooks are – apart from film footage, they must be the most vivid and lifelike records of Murray’s personality – but they are more than a gallery of eye-catching curiosities. They reveal salient aesthetic preferences. Murray collected images of a certain type, involving intricate geometry, recursive patterns and a flattening of perspective that abolishes the hierarchy of relationships between objects and presences. Sometimes photographs capture these patterns occurring spontaneously in nature or emerging by chance from elements of a scene. At other times they arise by design in artworks, reproduced on postcards.

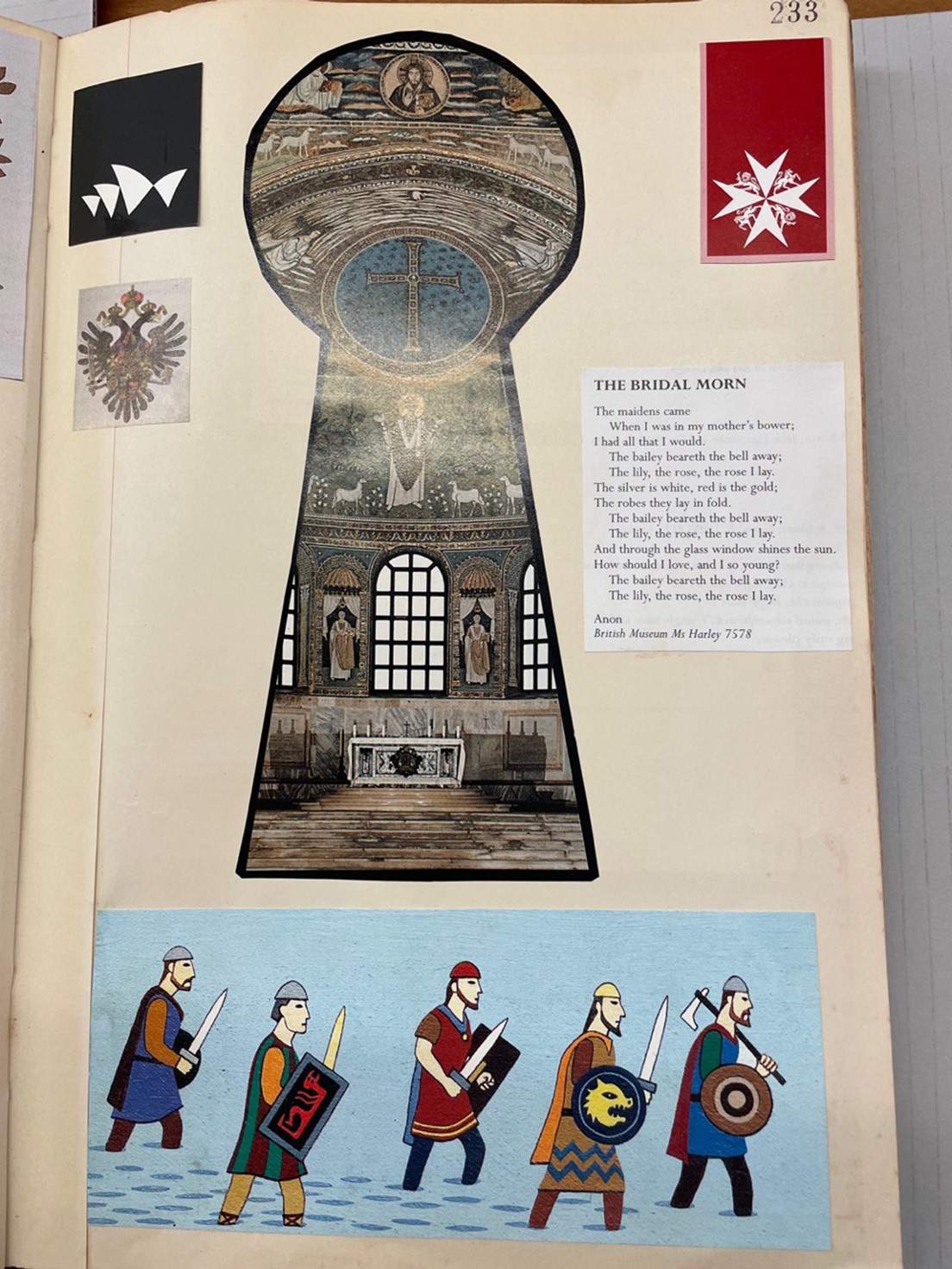

These patterns are keys to understanding Murray’s approach to shaping perceptions and ideas in language. It is noteworthy that a genre of artefact reproduced very often is the mosaic, in its Greek, Roman and Byzantine idioms, which epitomises the pattern that most attracted Murray: a whole is built from highly particular and equalised fragments. In addition to the many postcard reproductions, at some time between 1987 and 1998 Murray filled most of one scrapbook page with a magazine clipping of a mosaic of monumental scale (from the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna) and trimmed the image into the portentous shape of a keyhole:

In this image, the whole is perceived as a fragment, circumscribed by the barrier of solid, anonymous matter through which the ‘keyhole’ allows a tantalising glimpse. Is this glimpse clandestine and voyeuristic, or curious, snatched briefly in a moment’s intuition? There is an intense atmosphere of mystery in this scrapbook page. Yet it does afford one insight: we witness Murray confirming and rehearsing an instinct, reflecting back at himself a certain manner of interpreting reality. This page is a prompt to reconsider how Murray’s poetry arises out of its components of language; to consider how, in Clive James’s words, Murray’s poems ‘register, in words nobody else would quite choose, a perception that nobody else could quite have’.

With some notable exceptions, critics have treated Murray’s use of language as subordinate to its contents, even as they have asserted the archetypal ‘Australianness’ of both. It has been conventional to label Murray’s style as spoken vernacular and to praise its ingenuity – and leave it at that. Nevertheless, even if their terminology has differed, critics working decades apart have gleaned and described the same characteristics. This essay proposes a concept for strengthening and deepening the loose critical consensus regarding the poetry’s surface appearance.

Early critical responses to Murray’s poetry favoured thematic commentary and passed style over, for instance, calling it ‘a chaotic gleefulness’ consisting of ‘glorious gallimaufries of narrative, idiomatic direct-speech interjections and authorial comment’ (Ailwood 198), or praising ‘the rightness of detail with which [Murray] builds up pictures’ and ‘his fondness for the intricacies of language’ (Kinross-Smith 40–41) or admiring its ‘frequent leaps and excitements’ (Shapcott 387). Critics took time to grow comfortable with assessing Murray’s ‘gallimaufries’ as forms comprising functions and procedures. Only in 1983 could David Headon remark upon Murray’s habit of ‘accentuating the minutiae’ (71) of the Australian environment and his use of onomatopoeia to ‘realise certain conclusions’ (76), that is, marrying sound to sense to heighten the realism of a scene or to drive home a rhetorical point. And in 1991, Martin Leer remarked upon ‘an almost Baroque urge to populate the void with dense textures of objects and names’ (‘Imagined Counterpart’), which Leer saw as characteristic of such writers as Kenneth Slessor, Hal Porter, Barbara Hanrahan and David Malouf, in addition to Murray. Yet still these readings positioned Murray as working towards language with a predetermined aim, not out of language extemporaneously.

A crucial exception to these habits of gesturing at style or of placing themes ahead of it was David Malouf, who in 1982 emphasised Murray’s ‘voice’ as the poetry’s own ‘medium’ (307). Beyond a ‘foreground … filled with a dense bricolage of objects and facts’, Malouf understood Murray perceived a background primed with potential meanings,

called into existence by the poet’s interest in some phenomenon ‘out there’. [Each poem] is an essay, short or brilliantly extended with jokes, aphorisms, opinions, social observations, anecdotes, expressing a fixed view of things and springing to life in a language of baroque playfulness, a mixture of the slangy and the specialist, the common and the abstruse. (307)

Malouf also contended, ‘These poems are reflections, but of reality and the mind observing it, not a self’ (307), which is debatable, for there is a strong (if implicit) autobiographical element to Murray’s poetry. Depictions of teeming and associative thought processes are as much a reflection of Murray’s experience as images or anecdotes. Of importance here are Malouf’s presentation of style as the reflection of creative processes and his assertion that this can never be beside the point. With ‘an eye for small things as well as large, a delicacy of touch as well as epic sweep’, the flexibility and eclecticism of Murray’s cast of language accommodates ‘widely separated forms of experience’ (308), especially the division of loyalties between the bush and the modern city reflected in ‘the density of [Murray’s] argument, its packed and telescoped images, its rapid shifts’ between the ‘plain and common speech’ of Murray’s original rural community and the ‘abstruse references’ and ‘deliberate showoffishness’ of the intellect he cultivated in Sydney between the early 1960s and the early 1980s (307–08). In Malouf’s account, Murray’s ideas succeed not because of schematising (for Malouf, Murray ‘escapes his own formulae’) but because the poetry continually creates its own class-annihilating frame of reference (308).

Malouf warned against predicting how Murray’s poetry might evolve after 1982. Evolve it did, substantially, not always for the best from some critical standpoints, although more critics accepted style as a factor requiring focused attention. The critical reception of the work of the late 1980s and early 1990s is replete with analyses of Murray’s habits of language, which accept Malouf’s premise that language and its thought processes are the poetry’s sources and which usefully describe many of the poetry’s distinguishing features. John Barnie, for instance, made the crucial point that if the Australian vernacular was ‘the well-spring of Murray’s style’, then this was due to Murray’s having ‘internalised’ its ‘richness of proverb’, its ‘proverb-like metaphor’ and its idiomatic rhythms (23). A ‘sense of character’ is a result, not an origin, of language (24). Likewise, Alan Gould observed Murray’s use of proverb and aphorism as ‘building blocks’ from which the larger structures of poems were assembled (124). In Gould’s reading, for all the largeness and virtuosity of Murray’s creations, the essential value is concision: the poems achieve consistency not by the organisation of phases but by the integration of pieces (128). Martin Leer, too, read ‘dense textures of objects and names’ (‘Imagined Counterpart’ 5) as creating ‘a sense of dynamic, heightened stasis, of variation in monotony’ (‘Contour-Line’ 253). To these valuable observations from the 1990s we may add Amanda Tink’s from 2022. Tink draws a connection between Murray’s poetic technique and autistic perception, pointing to ‘line scan’, which is both Murray’s term for his method of creating a portrait of his autistic son Alexander out of factual statements each occupying a single line, and a photographic technique designed to produce detailed high-resolution images. It is arguable that the mechanism of ‘line scan’ can be detected throughout Murray’s work, reflected in the tendency to grasp details before generalities, resulting in representations that differ markedly from those formed via non-autistic ‘area scan’ methods that rely on generalities and received assumptions to make sense. Small facets determine large patterns, not vice versa.

Except that not all the patterns were large. A change came over Murray’s poetry from in mid-1990s. The poems grew noticeably shorter, their manner was less conversational, their tone more blasé, and the density of their material and image-making increased markedly (Pollnitz 43). Seldom did the early poems leave motifs standing alone, loaded with unspoken implications, though by the 1990s and the 2000s lone motifs not only formed the substance of short single poems but could also occupy whole sequences and spin varied meanings from a single thematic element. Clinical depression and other health problems in Murray’s later years may account partly for this reduction in scale and sustainment. Yet even if critics such as J. M. Coetzee considered the later ‘snapshots [and] records of sights that have arrested the poet on his travels’ to be ‘lesser work,’ the late poems’ style still made the most vivid impressions: Coetzee considered them ‘demonstration exercises’ of Murray’s sensitivity to sensory impressions and his ability to transform things into likenesses.

After all these piecemeal descriptions, what is the nature of Murray’s style? At its roots there is a paradox: distinct images or short phrases acquire a sense of interconnection. The dominant grammatical and imaginative principle is parataxis, not hypotaxis. A Murray poem, like a Murray scrapbook, accumulates images in ways that emphasise both their uniqueness and their relations with one another: experience is a sum of momentary perceptions, meaning a compound of suggestions, narrative a medley of thumbnail sketches.

I propose that the nearest corollary for this technique is the mosaic. A mosaic, composed from a myriad of roughly equal tesserae, is simultaneously rough and nuanced, fragmentary and unitary, mechanical in execution and dynamic in effect, and draws attention as much to the manner of its assemblage as to the resulting compound patterns and dimensions of meaning. Murray’s poetic treatment of language reflects all these characteristics. His approach to composition involves an extreme relaxation of conventional rules for construing meaning. The organising principle is verbal invention: the composing consciousness selects and combines words without exclusive regard for their conventional senses or relationships, positing the materiality of language as an aesthetic in itself (Hart 154–55). Excised from the traditional bonds of grammar, words achieve sense by juxtaposition and vividness of association. If we concentrate on these characteristics, we can quickly perceive that a mosaic technique developed early in Murray’s writing career, changed little, and became intrinsic to his poetry’s character, particularly its affection for the makeshift and ramshackle improvisations of farming life, its casual and playful manner and its dense interconnection of referents and effects. The boundaries between the familiar and the strange break down and reflect the perception – so Murray believed – of impulses, life-forces and sacred voices that recite and narrate existence.

The narrative element is crucial. Even when jumbled and confounding conventional structure, the language still constitutes an expressive form with a story to tell. Murray’s shorthand for this expressive form was ‘Wholespeak’ (‘A Defence of Poetry’ 25), language alert to and mirroring the bodily sensations of reality, allowing the mind to ‘half-consciously imitate the dance that is danced before us’ (A Working Forest 387), but the term rather glosses over the intricacies and sheer labour involved, and the origins of many poems in memory. Narrative is also the reason for describing such poems as mosaics rather than collages (or kaleidoscopes). Kevin Hart has observed that Murray’s poetry ‘draws its characteristic strength from snatches of colloquial speech, anecdotes, arguments, opinions, aphorisms’ (155). Often poems do seem to be made up of ‘snatches’ combined into strange conglomerates, as in a collage of clipped images glued together. Yet unlike a collage or a collection of ‘snatches’, the poems tend to coalesce along essentially coherent lines of thought, according to an integrated principle of design. As with the tesserae of a mosaic, fragments are gradually ordered by relationships of colour and texture to add up to something recognisable, larger and more expressive than the constituent pieces. And those pieces remain discernible, the single element displaying its own qualities and its contribution to the whole, incorporated but not fused. This is an unrefined method of image-making that works by leaving its basic processes and mechanisms on display. Mosaic poems are not so much written as assembled.

At the level of the word or phrase, this method thrives on the devices of synecdoche and onomatopoeia. The mosaics derive their vividness, as well as their sense of movement in quick turns and at glancing angles, from the focusing of literal and figurative sense into parts that stand for a whole and into the sound properties of certain words. For instance: ‘Lungless flies quizzing roadkill’ – from ‘A Levitation of Land’ in The Biplane Houses (Collected Poems 567) and ‘bees [that] summarise the garden’ – from ‘Nursing Home’ in Taller When Prone (Collected Poems 614). In both cases, Murray evokes the distinctive sounds of insects and their motions of flight, while also suggesting a special significance in their activities: in the former case, intensive investigation to find out what is worth scavenging, in the latter, a movement among standout flowers in an intimately familiar pattern. Precise on their own, both images contribute to larger structures of sense. The flies are ‘quizzing roadkill’ in the unnerving and question-provoking situation of a massive dust-storm sweeping over Australia’s east coast, described by the poem’s topsy-turvy title ‘A Levitation of Land’, while the garden that the bees are ‘summarising’ belongs to a nursing home whose inhabitants, afflicted with dementia, are experiencing the folding of memory in on itself. Both scenes are constructed from many diverse arresting phrases and images, of which the insect images are only a part, but these examples typify Murray’s technique of using self-contained images to build situations from focused effects.

Even if a mosaic poem does not advance the idea of the ‘Vernacular Republic’, or depict literally its scenery or emblematic characters, it still belongs to Murray’s mythical country insofar as it tests the expressive and imaginative capabilities of Australian English. Pithy description, condensed storytelling, dry and irreverent wit delivered with seemingly casual timing – the mosaic poems work their language much as the poor folk of Murray’s mythical landscape work their farms: making do with what is to hand, thinking loosely along playful lines of ‘bush logic’ (Headon 74). For an example, we can consider The Idyll Wheel – June: The Kitchens (first published in The Daylight Moon, 1987), a poem which is in fact a mosaic of mosaics, a chorus of Bunyah-region farming characters telling family stories. (The long poem ‘Crankshaft’ works in much the same way (Collected Poems 382–87)). Each stanza is cobbled together from mostly unpunctuated phrases, as here:

Poor Auntie Mary was dying Old and frail

all scrooped down in the bedclothes pale as cotton

even her hardworking old hands Oh it was sad

people in the room her big daughters performing

rattling the bedknobs There is a white angel

in the room says Mary in this weird voice And then

NO! she heaves herself up Bloody no! Be quiet!

she coughed and spat Phoo! I’ll be damned if I’ll die!

She’s back making bread next week Lived ten more years. (Collected Poems 287)

Each phrase is a quip, a shorthand view of an aspect of a person, event or experience. Certain phrases convey sharp images, via onomatopoeic metaphor as much as descriptive simile: ‘pale as cotton’. Auntie Mary is ‘scrooped down in the bedclothes’, the word ‘scrooped’ conveying not only Mary’s discomfort but also, by sound association, her withered and dishevelled appearance. Other phrases pinpoint implications of character and biography: Mary’s ‘hardworking old hands’ suggest lifelong self-denying labour, yet her daughters are ‘performing’ in their grief and distress, suggesting a generational decline in self-possession, with all that entails of emotional conflict. The absence of conventional distinction between each phrase establishes an equality of significance. The resulting flatness heightens the eeriness of the invisible angelic presence, the improbability of near-dead Mary’s reaction, and the amazement in the final observation that she ‘Lived ten more years’. The poem’s flatness emphasises the curtness of each phrase to create a matter-of-fact tone, which by contrast intensifies the sense that a miracle has occurred. No single quip encapsulates Auntie Mary’s story – it is their mosaic assembly that reveals the composite anecdote.

There may be limits to subjecting a mosaic poem’s arrangements of meaning to strict semantic or conceptual interpretation. The jumbling or breakdown of grammar and the myriad combinations of words and associations defy conventional technical principles, resulting in language that resists analysis or justification within standard frames of reference. The mosaic poems seek effects before codes and experience before analysis, working, in Murray’s conception, at the unmediated somatic level of sense-data before intellectual or rational interpretation (A Working Forest 387). The mosaic is not merely a method but a faithful depiction of the composition and experience of meaning. The mosaic is the message.

For an author who despised manifestos, cultural agendas and theoretical formulae, Murray was a ready advocate of his own ideas, but he shed little light on his practice and methods of writing. An interview with Robert Gray from 1976 is notable for Murray’s description of a non-linear, associative, unrefined method of composition: ‘The words seem to constellate. When I’m dead [that is, not satisfied with a draft] the words aren’t running together, making interesting little patterns. Sometimes I write around the edge of the page a lot of words that seem appropriate to the subject, and like flour around the edge of a mixing bowl they gradually get included in the mixture’ (71). In another interview in 1980, Murray described physically cutting written drafts into pieces and stapling the satisfactory parts together into ‘long snakes’, assembling elements physically to draw out possible associations, before re-typing them as a whole (Kinross-Smith 49). The NLA’s holdings confirm this: many such ‘long snakes’ survive among Murray’s drafts, notably the drafts of the ‘Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman’ sequence.3 The aim was to combine small perceptions and associations into summative compound reflections of perception, to mirror effects of sense-data aggregating into experience. In his interview with Gray, Murray explicitly stated that before philosophical matters, ‘everything in poetry must be an effect’ (72). As Murray elaborated, ‘The ensemble of effects in a poem calls into play our autonomic nervous system, the one we don’t consciously control, by bringing about a state of alert in us’ (A Working Forest 387), a ‘state of alert’ to stimuli and significances that constitute the ‘governing paradigms’ of whole realities (A Working Forest 151) which, Murray asserted, human beings interpret and comprehend as metaphors. By Murray’s terms, poetry (as an art and a practice) preserves ‘vivid, beautiful metaphor’ (A Working Forest 75) as an aspect of communication, but Murray cautioned that to have recourse to metaphor as a device was to risk allowing it to dictate beliefs and behaviour, which could result in violence and killing (A Working Forest 74–75, 375–76). Stylistic choices therefore enjoined ethical responsibilities. ‘I know a poet’, Murray wrote in the 1990s, possibly referring to Robert Gray,

who is careful to flag his every image with ‘like’ or ‘resembles’ or some such. The surf doesn’t fold its long green notes and cash them in foam-change on the beach, with him: rather, the waves of the surf are like long folded notes cashed in foam on the beach. […] My colleague doesn’t go beyond simile into the further reaches of metaphor because to telescope statements overmuch is to lie. He is scrupulous not to let metaphor collapse into identity. This is very Protestant of him, though he is not Christian. It is also very responsible, because metaphor is dangerous stuff, the more so, perhaps, as it becomes worn and baggy with overuse and we forget it is metaphor. (A Working Forest 74 – the ‘cash’ image of the ocean wound up in the poem ‘On Home Beaches’, Collected Poems 404.)

Unlike this other poet, Murray took the risk. The act of writing poetry, as Murray conceived it, was the attempt ‘to provide the poetic experience’ (A Working Forest 373), to record and recreate the fugitive guiding dimension in some graspable form. To convey this to others was an ethical as much as a technical exercise, the professional demonstration of Murray’s Catholicism. Murray was a Catholic convert and his belief in the presence of the blood and body of Christ in the consecrated Eucharist was intrinsic to, and inseparable from, his belief in poetry as the distillation (however flawed) of mystical experiences and supernatural influences. ‘Distinguo’, a four-line poem in Dog Fox Field (1990), is the epigraph for this philosophy: ‘Prose is Protestant-agnostic, / story, discussion, significance, / but poetry is Catholic: / poetry is presence’ (Collected Poems 341). Just as it is no accident that Murray’s scrapbooks are filled with mosaic images, so at the centre of the mosaic presented as being glimpsed through the keyhole, there stands the deity incarnate.

How and why did Murray’s mosaic technique and its consequences for his style come about, and how did the mosaic principle endure while other aspects of his methods changed? Was it the consequence of an autistic mind, as Murray himself believed? That is possible, but even if it is the case, autism alone did not bring the poems into being, nor direct Murray’s use of language towards the ‘poetic experience’ as he conceived it, nor single out poetry as Murray’s medium. Even if we accept Murray’s style as a reflection of habits of perception and thought, it can still be traced to certain literary sources, which in turn may suggest why Murray took to the mosaic technique so readily.

Murray was reticent, even coy, about his models. As with his methods, he seldom described them in depth. Occasionally, he indicated that poets of ancient Greece and Rome had endowed him with ‘a certain way of looking at the world’ (Kinross-Smith 49). Hesiod’s poems of Boeotia and Virgil’s Georgics and Eclogues showed Murray the exalted poetic possibilities the be found in agrarian life and closeness to nature. To Gray in 1976 Murray also conceded the influence of Australian predecessors Henry Kendall, Arthur Waley and Henry Lawson (70) in spirit at least, via archetypal conceptions of the Bush. Yet these are philosophical and not primarily stylistic influences. Certainly, none of them explains the uniqueness and the sheer strangeness of the mosaic technique.

In the Australian context, the poetic idiom closest to Murray’s is that of the Jindyworobak movement, whose exponents sought to weld English together with the structures and sounds of certain Aboriginal dialects. This was notionally a ‘decolonising’ effort (Fivefathers 61) to represent Australian realities in a native hybrid language. Roland Robinson, whose work was profoundly influenced by Jindyworobak aesthetics and long residence among Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory, Murray regarded as ‘an important stylistic pioneer’ for his renderings of Aboriginal stories in the vernacular ‘contact-English’ of remote communities (Fivefathers 62). Many products of the Jindyworobak project today seem acts of ventriloquism and appropriation. In 1977, Murray himself argued the Jindyworobaks’ ‘worthwhile project’ had been undermined by the ‘error’ of basing poetic-linguistic exercises on a single Aboriginal dialect out of hundreds, on the basis of romanticised and scholastically deficient interpretation (‘The Human-Hair Thread’ 9–10, 29: we today might see the ‘error’ as racially-inflected omission or elision). Even while distancing himself from the Jindyworobaks, Murray still made a case for ‘integrating’ Aboriginal concepts and stylistic elements into non-Aboriginal Australian poetry; in his own case, favouring emblematic phrases or epithets that concentrated the ‘partly synaesthetic signature-note of the Australian countryside’ into the material of poems (‘The Human-Hair Thread’ 22). Here, then, is one literary source for Murray’s predilection for aggregating language-effects into patterns of synaesthetic impression. Murray emulated the Jindyworobak practice of borrowing Aboriginal epithets and emblematic phrases in some works, most notably ‘The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ and the verse novel The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (1979), but he had given up the practice by the 1980s, possibly having recognised its still-colonial premise. Another Jindyworobak trait, the use of onomatopoeia to focus and emphasise metaphor in a colloquial idiom, is intrinsic to Murray’s work, although in this respect too he managed to avoid the Jindyworobak urge for overstatement exemplified by Roland Robinson in ‘Trunk Line Call’(with my italics): ‘Gull scream slashes wide open his sleep, / lashes him along his track winding way / round by the lake to ’phone, to shatter / her shuttered hurt’ (Murray, Fivefathers 88). Murray avoided such laboured internal doublings and near-rhymes. The Jindyworobaks’ influence on Murray might best be described as residual: instructive but not formative.

There is one presence in Murray’s descriptions of his influences, usually referred to obliquely and quickly glossed over, who offers a full rationale for an onomatopoeic, synecdochic and emblematic use of language in pursuit of a mosaic effect: Gerard Manley Hopkins. Murray first read Hopkins at secondary school and in his interview with Gray he said the experience ‘hit [him] like a bombshell’ (69). Murray did not elaborate how or why in that interview, but did in another in 1992, stating that Hopkins’s poetry modelled the art form for which he had been ‘casting about’ in his youth: it seemed the ‘live electric current’ in Hopkins’s language manifested the sheer intensity of experiencing existence (Missy 10). Hopkins’s poetry is known for having abandoned conventional idiom and prosody for immersive sensations and associations, reflecting his idiosyncratic ideas of ‘inscape’ and ‘instress’. Hopkins intended these elusive terms to stand for the patterns of sense he considered inherent in all things and experiences (‘inscape’) and the impulses that uphold, sustain and propel such patterns (‘instress’) (Chevigny 142–43). As in Murray’s work, traditional structures of relationship and sense-making are dissolved. Elements of a scene and an onlooking consciousness are left to blend or collide in an agglomeration of impressions, as in ‘The Windhover’, to quote only one of countless examples:

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion. (Poems 29)

The properties of ‘inscape’ and ‘instress’ apply as much to the rendering of phenomena as to the phenomena themselves (Chevigny 142). ‘Inscape’ is the material of language, ‘instress’ its rhythmic impulses and combinations, and each depends on and reinforces the other to produce the ultimate effect: a composite made up of composites.

Critics have established the relationship between Hopkins’s ‘inscape’ and ‘instress’ and Murray’s ‘Wholespeak’, as achievements of perception and insight via the accumulation of fragmentary details (Barnie 1985). Most salient in this line of analysis have been Nils Eskestad and Stephen McInerney, both of whom conclude (from different precepts) that Hopkins and Murray envisaged poetic composition not as a rhetorical endeavour but as a metaphysical performance, an act of embodiment registering both the meaning and the presence of subject matter. For McInerney, the connection is mystical-philosophical, a reflection of the Catholic belief in the divine incarnate in earthly material, as in the Eucharist (171–231; Missy 10). For Eskestad, the connection is a question of mimicry: Hopkins melts down and reconstitutes language to mimic the ‘soundscape’ or ‘music of embodiment’ (including hints of the divine) which he perceives in material, and Murray, in mimicking Australian material and idioms, mimics the example of Hopkins. Ian Cooper argues a similar case, asserting that Hopkins is ‘behind’ Murray’s depictions of landscape: the equalising and flattening effect of reconstituted language (as in the anecdote of Auntie Mary) is a derivation from Hopkins that satisfies Murray’s desire ‘to be in the world of perspective but freed from its diminishments’ (205). Bridging both the mystical-philosophical and the linguistic-representational sides of the question, Murray himself, reflecting the influence of Hopkins, described the mystical experience of the Eucharist as ‘metaphor taken all the way to identity’ (Alexander 106). If Murray was a mosaicist, then he learned the ethos and the technique from Hopkins.

Hopkins’s influence on Murray seems to have operated on all these levels at once (religious-mystical, material-embodying, perspective-flattening), although historical evidence weighs in favour of Murray valuing Hopkins first for linguistic ingenuity as the source of religious-mystical experience. That is, it appears it was not chiefly Catholic sympathies which made Hopkins’s mosaics so meaningful to Murray. For one thing, Murray’s ‘bombshell’ encounter with Hopkins’s poetry at school in the 1950s predated his conversion to Catholicism in the 1960s (Alexander 56, 84–85, 107) and the appeal arose from sensory appreciation; at the time of that first encounter, as Murray put it, ‘things that I knew about were being used as imagery in poetry’ (Gray 69). Even once Murray had embarked on his poetic career, the record seems to show that the religious-mystical dimension was contingent on the handling and possibilities of language, down to the single word and sometimes even the single syllable. Murray’s mysticism arose out of language – he did not direct mysticism towards it.

Striking evidence for this order of preference exists in the NLA’s holdings, on a cardboard back-board of a notepad dating from 1973 or 1974. This was one of several back-boards on which Murray jotted down isolated phrases, images, ideas or aphorisms as they occurred to him while drafting and re-drafting poems on the notepaper pages – he used the back-boards to preserve fresh tesserae for future mosaics. On this particular back-board, among fragmentary musings and maxims – one, ‘You can’t poe a lie’, was adapted for the poem ‘Poetry and Religion’ some years later (Collected Poems 265) are these words, with Murray’s underlining: ‘Morning’s minyan (from “The Windhover”)’.4 The quotation is a phoneticised rendering of the phrase ‘I caught this morning’s minion’ in the opening line of ‘The Windhover’. The word ‘minion’ characterises the titular hovering kestrel as the servant of daybreak and, allusively, via a play on the French mignon, the darling of daybreak. Yet by transposing ‘minion’ into ‘minyan’, Murray registers a third dimension embedded in Hopkins’s sound pattern, a spiritual one: minyan, in Hebrew, is the quorum of ten required for a Jewish prayer gathering. Thus by a mechanical relation, minion/minyan, in Murray’s reading Hopkins’s kestrel embodies and focuses the daybreak’s spiritual uplift. By the time Murray made this manuscript note in 1973 or 1974, his poetic attachment to and religious identification with Hopkins were of long standing, so it is no surprise to witness Murray finding fresh significance in Hopkins’s work. The surprise is in the location and procedure of that significance. Here, the marriage of sound to sense, and the perception of new sense, occur by mechanical rearrangement – minion/minyan – and are reflexive and associative before they are rational. It is the manipulation of syllables as sound units, and words as their composites, that assembles the larger dimension. This is the root principle of the mosaic technique in action.

Murray almost certainly had other technical models. The work of Dylan Thomas, another Hopkins inheritor, may have left its mark, particularly Thomas’s habit of creating compound images and fused associations through unconventional participle clauses, such as the celebrated ‘mussel pooled and heron / Priested shore’ (‘Poem in October’, Collected Poems 86). The ‘stream of consciousness’ narrative style as developed in the heyday of modernism by such authors as Virginia Woolf, Djuna Barnes and James Joyce may also have played its part. Murray’s reading during his university years was excursive and eclectic (Alexander 67–68) and it is plausible that he acquired something from one or more of those authors. Even so, Murray’s notion of gleaning experience from small fragments differs from Woolf’s idea of emotions meeting, colliding and disappearing in ‘astonishing disorder’ (Woolf, 23). There is an order to Murray’s multifarious reflections of experience, in the form of the mediating consciousness of the poet himself – the mind observing the reality, to paraphrase David Malouf (307). Murray’s technique predates the poetic trend of ‘Martianism’, an idiom that takes its name from Craig Raine’s poem ‘A Martian sends a postcard home’ (1979) and that finds fresh significance in mundane activities by freeing language and perception from ‘habitual knowledge’ – often to comical and satirical effect, and Murray frequently enjoyed the comedic side of satirising the absurdity of many Australian assumptions and pretensions. But like ‘Martianism’, Murray’s technique may have some roots (perhaps unconsciously, via forgotten or undocumented encounters) in the Russian principle of ostranenie, an older form of defamiliarisation whose name translates as ‘making strange’ (Jenkins 2023).

Whether or not Murray was influenced directly by ostranenie or later found influence or confirmation in ‘Martianism’, his work finds parallels in both insofar as the defamiliarising effect of the mosaic technique is an aesthetic principle (Hart 151, 154–55), distinctly preferred and followed. Murray does not feature in Gerald L. Bruns’s major study of modernist parataxis, Interruptions: The Fragmentary Aesthetic in Modern Literature, but the mosaic technique displays almost all the key characteristics of fragmentary and associative poetics that Bruns derives from the writings of Friedrich Schlegel and diagnoses in the work of James Joyce, Maurice Blanchot, Samuel Beckett and others. Murray’s mosaics do indeed constitute Bruns’s concept of ‘a form that absorbs (and neutralises) all distinctions’ (5), but although mosaic patterns of language are free ‘of any principle of subordination’ (7) and its constituent parts enjoy ‘freedom or autonomy in their juxtaposition’ (44), the mosaics are not ‘free of the law of noncontradicition’ (7). In Murray’s mystical worldview, the autonomy of words is still a form of service to a different order of significance, which the poetic consciousness is compelled to affirm. However imperfect Murray may have found language as his medium (‘Everything except language / knows the meaning of existence’ (Collected Poems 551)) he nonetheless took the same crucial step as Bruns’s subjects, in accepting that conventional grammar was too limited to grasp the significance insisting on his attention and could be dispensed with. All that remained was to adapt the particles of language into forms that followed more closely, more faithfully, the patterns of reality that were making themselves felt. Ironically, the fragmentary, paratactical and associative aesthetic of the mosaic is Murray’s way of being literal.

Many of Murray’s poems may appear extemporaneous and reflexive and indeed the manuscripts in the NLA reveal that over decades Murray often set down fragments of phrases or lines in a rush, usually on the cardboard back-boards of his notepads, before and during the process of elaborating more coherent structures such as sentences or stanzas into the recognisable shapes of poems.5 The moment of transition – the act of combining the rudiments on the cardboard into sentences, stanzas and poems on the paper – is seldom captured in the materials held in the NLA. (Perhaps it is captured more often in materials outside the NLA but not yet identified.) Nevertheless, by its very nature as a process of assembly, the mosaic technique involves comparison, selection and decision. Murray’s conception of poetry as the result of a non-rational synaesthetic ‘trance’ closely resembles the hyper-expressive fugue state of the ‘stream of consciousness’, but more than one level of consciousness was involved in Murray’s process. In assembling pieces and finalising poems, Murray had reasons, however inchoate, to prefer one disposition of tesserae over another. If the NLA manuscripts rarely capture the ‘trance’, they are replete with examples of ‘the adjustments after’ (Collected Poems 458). Reconstructing how Murray realised his preferences would require an intensive archival study, but the readiest documents of the mechanics of assembly are the final poems themselves. To paraphrase Paul Valéry, the distinctiveness of a mosaic is that it draws attention to the art of making as much as to the thing made (1022).

In the space remaining, we will consider how Murray’s mosaic technique evolved.

Murray’s first collection, The Ilex Tree (1965), a joint volume with Geoffrey Lehmann, reflects some identification with W. B. Yeats in sublimating situations and emotions into myths and ‘phantasmagoria’, which Murray took some years to leave behind (Alexander 120; Pollnitz 46–47). Several poems in The Ilex Tree are laden with Celtic Twilight symbolism and intoned with defeated heroism. (Certain poems which displayed these tendencies, such as ‘Love After Loneliness’, Murray ended up leaving out of his Collected Poems.) Yet the volume also displays the first steps towards a mosaicist handling of language. Late in The Ilex Tree there is a marked change in style. On the surface, this correlates with Murray’s deliberate and often-explained choice to treat poetry as an expression of his intimate experience of the Australian rural world. Less overtly, the change probably reflects the ‘bombshell’ effect of Hopkins receiving more studied attention and being transposed into action. The examples are small, but they suggest that Murray was quickly coming to understand the linguistic and technical potential that Hopkins’s mode of writing could offer him. It was in the sequence ‘Driving through Sawmill Towns’ that Murray found his way of loosening the bindings of literal meaning around statement and description, drawing more on the sound-texture of language to evoke subjects. Perhaps this sudden stylistic change was brought on by the need to fill space left by the withdrawal of a third poet, Brian Jenkins, from the joint Ilex Tree venture (Alexander 120) – the sudden rush to complete the volume may have brought special focus to Murray’s instincts. Consider in this example the alliteration – a Hopkins hallmark – stressing the depiction of saw-logs, and also the precise onomatopoeic effects of certain verbs (‘swerve’, ‘sags’) in a free stanza calculated to reflect the speed and glancing angle of view from a moving car:

the swerve of a winch,

dim dazzling blades advancing

through a trolley-borne trunk

till it sags apart

in a manifold sprawl of weatherboards and battens. (Collected Poems 10)

The same sequence contains a reference to ‘calendared kitchens’ (11), a compound image that focuses the lives of the sawmill towns’ women into small rooms where time is regimented but unmarked by experience. ‘Driving through Sawmill Towns’ is not entirely a mosaic poem but its approach to narrative and description, achieved not by linear sequencing but by allowing focused images to accumulate, marks it as the forerunner of the dozens of true mosaics, many of them gigantic, that would follow.

Murray developed facility in creating mosaics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The technique then changed little in almost thirty years. Not every poem of Murray’s from the late 1960s to the late 1990s is a mosaic, but more than half either consist entirely of mosaic language or slip into it for long stretches in the effort to suggest a reality beyond the literal present. Discursive and ruminative poems veer off into fugues of thought; landscapes are depicted via accumulation of detail rather than description. The poems achieve these effects having shed the baggage of an obvious debt to Hopkins. Alliteration, in particular, is abandoned, in favour of a greater variety of evocative sound-combinations and more naturalistic reflection of everyday speech. Murray also married the mosaic technique with another aspect of his style that is not a feature of Hopkins’s or Dylan Thomas’s, the aphorism. Out of many of these mature mosaics burst sudden flashes of insight and conclusiveness, as though the mosaic represents the mulling and searching, even sometimes the chaos, that leads the poet to realise some intuition the rational mind can neither attain nor express otherwise.

The poems from Murray’s mature period that work in this way include such celebrated sequences as ‘Toward the Imminent Days’ (Poems Against Economics, 1972) and ‘The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ (Ethnic Radio, 1977) but these immense structures stand on basic principles tested and elaborated in smaller forms. Kevin Hart has argued persuasively that the basic effect of Murray’s rendering of a given subject in reconstituted language is a ‘vivid defamiliarising’, citing as an example the poem ‘Second Essay on Interest: The Emu’, which characterises the large bird’s shaggily-feathered body as ‘a huge Beatles haircut’, its neck as ‘an alert periscope’ and its knees, relative to its feet, as being oddly angled ‘backward in toothed three-way boots’ (Collected Poems 201; Hart 151). These denser ‘defamiliarising’ poems, gazes that deconstruct the character of their subjects and reassemble it according to the poet’s idiosyncratic perception, are the ‘demonstration exercises’ in likeness-making that Coetzee asserted were what remained of Murray’s best poetic faculties after 1992. Whether or not we accept Coetzee’s assertion of a decline in Murray’s work (which Hart startlingly alleged began after 1977 [155]), the notion of ‘exercises’ is a useful one. From the 1970s onwards, it was imagistic poems such as ‘Second Essay on Interest: The Emu’ which nourished the techniques that sustained the larger essayistic poems, in a process Hart described as ‘expansion’, in which verbal invention ‘relaxes organisation and offers rhetorical excess as a principle’ (155). Where the shorter poems focused and rehearsed ‘sharp, defamiliarizing imagery’, practising the breaking-down of experience into tesserae, the large-scale poems then drew on the lessons learned to assemble their own tesserae into vast patterns, sustaining virtuoso performance.

Before ‘The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’, for instance, there was ‘The Powerline Incarnation’ (Ethnic Radio 1977), a mosaic poem that is just as densely assembled but even more intensely driven than its larger successor, shooting off at breakneck speed to depict the experience of electrocution as though from inside, in a rehearsal of what turned out to be the ‘highway-driving’ momentum that underpins the ‘Bulahdelah-Taree’ sequence. ‘The Powerline Incarnation’ is the ultimate in what the mosaic technique can achieve in depicting mental activity, in this case, sheer frenzy. In being electrocuted, the consciousness becomes one with the current and travels everywhere the current travels:

When I ran to snatch the wires off our roof

hands bloomed teeth shouted I was almost seized

held back from this life

O flumes O chariot reins

you cover me with lurids deck me with gaudies feed

my coronal a scream sings in the air

above your dance you slam it to me with farms

that you dark on and off numb hideous strong friend

Tooma and Geehi freak and burr through me

rocks fire-trails damwalls mountain-ash trees slew

to darkness through me I zap them underfoot

with the swords of my shoes

[…]

passion and death my skin

my heart all logic I am starring there

and must soon flame out

having seen the present god

It who feels nothing It who answers prayers. (Collected Poems 122–23)

The concluding lines resolve the extreme tension between ordered and disordered thought. The mystical insight that emerges confirms the larger pattern, the divine presence, that Murray so often insisted was manifest in material everywhere.

The maturing of the mosaic technique fostered two other fundamental aspects of Murray’s work: the evocation of character through the mingling and agglomeration of characteristics (rather than by demonstration through actions or words) and, as an offshoot of this approach to character, the depiction of animal life as an amalgam of sensations and instincts, a spontaneous form of consciousness living on instinct and not ideas. We find the principle of character-as-characteristics fully at work in the sequence ‘Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman’ (The People’s Otherworld, 1983):

Shaking in low slow flight, with its span of many jets,

the combine seeder at nightfall swimming over flat land

is a style of machinery we’d imagined for the fictional planets:

in the high glassed cabin, above vapour-pencilling floodlights, a hand,

gloved against the cold, hunts along the medium-wave band

for company of Earth voices; it crosses speech garble music –

the Brandenburg Conch the Who the Illyrian High Command –

as seed wheat in the hoppers shakes down, being laced into the thick

night-dampening plains soil, and the stars waver out and stick. (Collected Poems 192)

The conceit is that the combine seeder, with its unusual shapes and intricate mechanical actions, is a machine outside the earthly-conventional, but its weird otherworldliness is achieved solely by a conglomeration of onomatopoeic effects and allusions to science-fiction and incongruent musical sounds. Murray selects emblems of Baroque counterpoint, via the reference to J. S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, and the tumult of exuberant freestyling rock, via the reference to The Who – further testimony, in concentrated form, to Murray’s eclectic repertoire of references packed with associations that deepen the mechanics already at work. Murray claimed not to know much about music (see, for instance, ‘Music to Me Is Like Days’, (Collected Poems 462–63)), but the reference to Bach alone suggests he understood more than he admitted. A Bach fugue, a contrapuntal web that builds ever-greater structures and reveals startling interrelations even as it seems to defy design and containment, is a strikingly apt parallel for the elaborate mechanism of the seeder as Murray conceives it. Yet, Murray qualifies the ‘Brandenburg’ emblem immediately by substituting the expected word ‘Concertos’ with the word ‘Conch’. The implication is that the seeder’s sound may be fugally complex, but it is not delicate: it is more like the blast of a blown conch shell. The associations contained within these small words are dense, multifarious and finely calibrated. The result is a cacophony of concepts as well as effects, a highly sophisticated reinforcement of the alien qualities already evoked via the surface of language. Murray could refer to and draw upon music advisedly, if it fitted the pattern in play.

The same principle of dense agglomeration applies in a depiction of a milk lorry in the poem of that name in The Daylight Moon (1987):

Long planks like unshipped oars

butted, levelling in there, because between each farm’s

stranded wharf of milk cans, the work was feverish slottingof floors above floors, for load. It was sling out the bashed

paint-collared empties and waltz in the full,

stumbling on their rims under ribaldry, tilting their big gallonsthen the schoolboy’s calisthenic, hoisting steel man-high

till the glancing hold was a magazine of casque armour…. (Collected Poems 252)

We find it at work again in ‘Lyrebird’ in Translations from the Natural World (1992), a collection composed almost entirely of mosaic poems intended to reflect reality as experienced by non-human consciousnesses, in this case, the bird whose song consists of mimicry of other birdsong and sounds:

Liar made of leaf-litter, quivering ribby in shim,

hen-sized under froufrou, chinks in a quiff display him

or her dancing in mating time, or out. And in any order.

Tailed mimic aeon-sent to intrigue the next recorder,

I mew catbird, I saw crosscut, I howl she-dingo, I kink

forest hush distinct with bellbirds, warble magpie garble, link

cattlebell with kettle-boil… (Collected Poems 358)

With ‘Lyrebird,’ the conventional relationship between word and referent is entirely unstuck and reassembled. The lyrebird-consciousness, predicated on sound-mimicry (‘link / cattlebell with kettle-boil’), immerses itself in associative noun-verb constructions (‘I mew catbird, I saw crosscut, I howl she-dingo, I kink / forest hush distinct with bellbirds’) which are mirrored in the evocation of the lyrebird’s own gaudy physicality (its white ‘froufrou’ tailfeathers ‘quivering ribby in shim’). The bird’s reality is not merely depicted as a mosaic. The mosaic is its reality.

Poems such as ‘Lyrebird’ came to dominate Murray’s production in the 1980s and 1990s. The declaration ‘poetry is Catholic: / poetry is presence’ seems to have marked Murray’s own realisation that he was moving away from large-scale landscape-dreaming, ancestry-evoking and ruminative scene-setting. ‘Presence’ is indeed the title of the whole ‘Translations from the Natural World’ sequence of animal poems. The overriding aim, by the 1990s, was to strive to represent consciousnesses other than the poet’s own, to do some justice to other experiences of living. Even if the conceptual emphasis changed, the methods did not: Murray’s interpretations of the imaginative lives of other beings still crystallised as mosaics. Murray’s poignant exploration of his son Alexander’s experience of autism, the poem ‘It Allows a Portrait in Line-scan at Fifteen’, is not quite the climax of the mosaic technique’s evolution, but it is the poem that most actively and neatly draws attention both to the technique’s principle and its mechanism. ‘Line-scan’ is the action of the mind building up a composite image from single-line observation, a precise analogue of a mosaic building a composite image from single tesserae.

This turn towards other lives, particularly those of animals, seems to have been due to long periods of self-disgust arising from severe clinical depression. Murray described his attempts to ‘enter imaginatively into the life of non-human creatures’ as ‘giv[ing] my stupid self a rest’ (Killing the Black Dog 14). The result of that turn, the climax rehearsed in that ‘line-scan’ portrait, is the verse novel Fredy Neptune (1998), which explodes the dimensions of all Murray’s previous work but does so on the same principle as ‘The Kitchens’ and ‘Crankshaft’, by constructing large mosaics from small ones. Fredy Neptune is narrated in the first person, drawing on Fredy’s own memories and mental landscape. The book opens with Fredy describing a slide show of family photographs:

That was sausage day

on our farm outside Dungog.

There’s my father Reinhard Boettcher,

my mother Agnes. There is brother Frank

who died of the brain-burn, meningitis.

There I am having my turn

at the mincer. Cooked meat with parsley and salt

winding out, smooth as gruel, for the weisswurst.Here’s me riding bareback in the sweater

I wore to sea first.

I never learned the old top ropes,

I was always in steam. Less capstan, less climbing,

more re-stowing cargo. Which could be hard and slow

as farming – But to say Why this is Valparaiso!

Or: I’m in Singapore and know my way about

takes a long time to get stale.My German had got me a job

out of New York on a Hansa freighter… (13)

The motion of slide succeeding slide defines all the movement of the yarns and adventures that follow: from family photos, via memory and anecdote, into the adventure, with no narrative signposts. Fredy’s experiences unfold as a succession of vignettes, single images, expressed in the familiar offhand manner, which flicker over one another to give the impression of narrative drive and motion in retold memories.

Fredy Neptune might be one gigantic mosaic, but it is also among the last of its kind. Probably the last ‘true’ mosaic poem is ‘The Images Alone’ (Poems the Size of Photographs, 2002), an amalgam of seemingly unrelated ideas that hang together in a purely fantastical evocation of abundance and sudden, though mysterious, understanding:

Scarlet as the cloth draped over a sword,

white as steaming rice, blue as leschenaultia,

old curried towns, the frog in its green human skin;

a ploughman walking his furrow as if in irons, but

as at a whoop of young men running loose

in brick passages, there occurred the thought

like instant stitches all through crumpled silk:as if he’d had to leap to catch the bullet.

A stench like hands out of the ground.

The willows had like beads in their hair, and

Peenemünde, grunted the dentist’s drill, Peenemünde!

Fowls went on typing on every corn key, green

kept crowding the pinks of peach trees into the sky

but used speech balloons were tacky in the river

and waterbirds had liftoff as at a repeal of gravity. (Collected Poems 512)

From this point the mosaic technique, as we have hitherto understood it, ceased. Where previously the large structures of the poems had accumulated out of ‘accentuate[d] minutiae’ (Headon 71), from the early 2000s to the end of Murray’s life in 2019 the poems seemed to consist of minutiae only.

Murray’s vernacular idiom was as rich in evocative and associative potential as ever, but the poems’ field of vision seemed to narrow from the mosaic, the larger composite image, down to the single piece or small collection of pieces. From Poems the Size of Photographs to the posthumous collection Continuous Creation (2022) Murray’s poems became severely briefer and denser. A few quasi-mosaics occasionally appeared, such as ‘A Dialect History of Australia’ (The Biplane Houses, 2006) which consists of place names, beginning with solemnly punctuated Aboriginal sacred place names and picking up speed with the coming of Europeans: ‘Bralgu. Kata Tjuta. Lutana. // Cape Leeuwin Abrolhos Groote Eylandt. // Botany Bay Cook Banksia Kangaroo Ground’ (Collected Poems 562). Here, Murray gives order and relationship to his tesserae by applying the ‘grammar’ of the chronological order of their historical associations, rather than accumulating composite images. The short sequence ‘The Scores’ (Poems the Size of Photographs, 2002) works on a similar principle, charting social change over twenty-year leaps by assembling historically associative images around a single motif, a flower, as an emblem of an era or generation: ‘golden wattle’ at Federation, poppies in the wake of the First World War, ‘Singapore orchid’ wreaths in the heat of the second, all the way to glitzy Edna Everage-style ‘flung gladioli’ in 1981 and ‘Olympic Gold roses’ in 2001 (Collected Poems 531–33). A further late quasi-mosaic is ‘Infinite Anthology’ (Taller When Prone, 2010), an assemblage of bizarre dictionary definitions. Yet the variety and integrity of the mosaics were giving way. Increasingly, the poems concentrated on single images, reciting their possibilities but ultimately leaving ideas behind or not fixing them into a final composite, as in ‘Manuscript Roundel’ (previously titled ‘The Medallion’, Taller When Prone, 2010):

What did you see in the walnut?

Horses all harnessed criss-cross

and a soldier wearing the credits

of his movie like medal ribbons.

An egg there building a buttery

held itself aloft in his hands –

the horse-straps then pulled the nut shut. (Collected Poems 640)

This poem is a mosaic in the strict sense of an assemblage of small tesserae, but the one essential quality, the final composite image whose meaning the poem clearly encapsulates, is missing. (I once heard Murray read ‘Manuscript Roundel’ in public. On finishing, he paused, then protested, ‘I don’t know what it means!’)

Still there were moments when Murray would expand and elaborate a single image or motif into a larger picture, as though ruminations on a given element were spilling over into medleys of variations on a theme, as in the sequences ‘Leaf Brims’ and ‘The Nostril Songs’ in The Biplane Houses. Each stanza of ‘Leaf Brims’ presents a tableau scene, a moment of decision or unknown but possibly historic potential, each different from the others but all marked with the ominous refrain ‘the truth is years away’ (Collected Poems 555). ‘The Nostril Songs’ is a loose series of sketchy riffs on the idea (oddly) of noses. Also in The Biplane Houses, Murray included two sets of extremely condensed but lightly-handled three- or two-line poems capturing single images, ‘Twelve Poems’ and ‘Lateral Dimensions’, precisely in the style of Robert Gray; for comparison, see Gray’s ‘13 Poems,’ ‘18 Poems’ and ‘15 Poems’ in Creekwater Journal (1973). Quite possibly, these were Murray’s homage to his friend and colleague. Yet by the years of Taller When Prone (2010), Waiting for the Past (2015) and Continuous Creation (2022) even the elaboration of individual fragments had thinned out, the poems displaying no less immediacy – onomatopoeia was still the supreme device – but ever less energy for self-sustainment. It was as though the latter poems fulfilled Fredy Neptune’s offhand remark at the end of his immense life-story, ‘There’s too much in life: you can’t describe it’ (Fredy Neptune 265).

Was this attenuation a consequence of old age and infirmity? Or did Murray actively decide to leave his mosaic style behind? ‘Routines of decaying time / fade’, Murray wrote in ‘Self and Dream Self’ in Waiting for the Past, ‘and your waking life / gets as laborious as science’ (62). Even this blunt statement of fatigue leaves questions in its wake, for Murray left ‘Self and Dream Self’ out of his last Collected Poems. Was the poem too despondent? The thinning down of Murray’s style was probably not all due to weariness, or if it was, the weariness was derived not only from the long life of the body. Murray seemed to believe that his Australia had given up or lost its plenitude. On either side of the ‘new motorway’ not far from his home in Bunyah, ‘plastic shrub-guards grow bushes / to screen the real bush, / to hide the old towns / behind sound-walls and green’ (‘As Country Was Slow’ Collected Poems 608). Pervading these last poems are motifs of concealment, bypassing and moving on. They create a poignant and regretful sense of undue obsolescence, an ultimate ‘relegation’, as Murray might have put it (‘And Let’s Always’), by the victorious governing metaphors of progress and development. If we approach Murray’s last collections from this point of view, then it is no coincidence that he construed this creeping uninterest as one last mosaic, a mirrorball:

…now song and story are pixels

of a mirrorball that spins celebrities

in patter and tiny music

so when the bus driver restarts

his vast tremolo of glances

half his earplugged sitters wear

the look of deserted towns. (Collected Poems 71)

This mirrorball symbolises lonely lives that are made superficial and lived cheaply, shut off from one another. The mosaic has become a symbol of an atomised culture.

Even if much of the poetry from Murray’s final years struck a melancholy note, that need not constitute his parting statement. There is no question that Murray’s impulse to agglomerate ideas into large, elaborate and virtuosic mosaics did attenuate towards the end, but we only perceive that change in light of the works written before the difference set in. What I have tried to do is to offer a brief history of an instinct and a technique that essentially unify Murray’s work, by their dwindling as much as by their awakening and maturity. As with the mosaic cut into the shape of a keyhole and pasted into Murray’s scrapbook, every tessera – more or less outstanding in quality, glimpsed in greater or lesser context, understood more or less fully – belongs. The parting statement is not the last piece but the whole picture.

Acknowledgements

I thank Les Murray’s literary executor, Margaret Connolly, for her kind permission to quote from the scrapbooks and the drafts held in the National Library of Australia. I also thank the staff of the Library’s Special Collections area for their assistance during my research for this article.

Footnotes

-

Dylan Thomas, letter to Pamela Hansford Johnson, 2 May 1934 .

↩ -

See also John Goodby, The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Under the Spelling Wall (Liverpool UP, 2013), p. 123: ‘In a Thomas poem, words and verbal units often play a role which is more active and structure-creating, less subordinated to a pre-existing end or goal than is usual, even in poetry.’

↩ -

Les Murray, manuscript of ‘Machine Portraits with Pendant Spaceman,’ Papers of Les Murray, MS 5332, Box 9, File 63.

↩ -

Les Murray, handwritten note on cardboard notepad back-board, Papers of Les Murray, MS 5532, Box 4, File 25.

↩ -

Les Murray, numerous poetry manuscripts, Papers of Les Murray, MS 5332, Boxes 3–4; Box 9; Box 39; Box 52; Box 53, File 378.

↩